It's Raining Returns: Here Are 7 Ways to Wring Out Revenue

By Ian McCue for Brainyard

June 11, 2020

In short:

In 2019, U.S. shoppers returned merchandise worth more than $300 billion, with a significant chunk of those items ending up back in the hands of distributors.

While chain of ownership varies by business model, for D2C, B2B and traditional retail CFOs, it’s a good time to review contract terms and evaluate the potential for a spike in returns as the economy reopens.

Finance teams should take this opportunity to gain insight into how their companies and distribution partners manage the reverse logistics process, including average losses.

Ecommerce represents tremendous promise for wholesale distributors and business-to-business sellers, including those that added a direct-to-consumer channel to maintain revenue during the pandemic.

For B2B distributors specifically, ecommerce represented 12% of 2019 sales, according to Digital Commerce 360. And that opportunity is poised to explode in the next five to 10 years — B2B Next predicts 40% of B2B sales will happen online by 2028.

Predictably, as B2B companies sell more online, they see more returns. And now, a real downpour may be brewing.

Caitlin Roberson, VP of marketing at reverse logistics services and software company Happy Returns, said customers send back, on average, 30% of online purchases, with a return rate as high as 50% for some apparel brands. Compare that with the 8% to 10% return rate for in-store purchases.

Right now, return rates are artificially, but temporarily, affected by retail store closings, worries about COVID-19 contamination and stockpiling. As we reopen, ecommerce sellers could see a spike, and CFOs need to understand how their companies will handle refunds.

“My high-level thought is, much like the airline industry is facing an unprecedented lag in demand right now, we’re actually seeing in a lot of areas unprecedented increases in demand that are far beyond usage,” said Janet Schijns, CEO of distribution consultancy JS Group. “There’s even panic buying in the tech channel around endpoints for security, routers, servers, motherboards — things that people are surmising are going to not be in stock. If they don’t use them, and this begins to tamp down, they’re going to return them.”

Most companies will start the clock on 45-, 30- or 15-day return policies when restrictions lift. In cases where the return window is more open, there’s even more potential for chaos.

“People are not going to rush to send those items back now,” Schijns said. “They’re going to rush to send those items back when they no longer feel the need to stockpile to meet potential needs for customers. The conversations we’re having is, how do [retailers and distributors] manage that stock, knowing that demand seems overly high in some areas? Do they replenish, which does have some lead time, and then get all that stock back? And if so, how do they afford to pay everybody who returns, because they don’t want to ruin that relationship?”

As we’ve discussed in context of the KPIs CFOs are now monitoring, finance teams are watching their inventory levels more closely, with this metric being especially critical for finance leaders who lacked visibility into warehouse, distribution center or stockroom inventory levels in the pre-COVID world.

“Regardless of what comes to be, that actually underscores the importance of the CFO’s role as it relates to returns,” said Roberson. “There’s not a clear owner today inside of an organization about who is responsible for handling returns effectively — and by ‘effectively’ I mean in terms of revenue, in terms of costs and in terms of sustainability and customer lifetime value. I think it’s incumbent upon that head of finance ... to take ownership of it, identify best and worst practices and then come up with a holistic strategy that thinks about returns through the lens of the business.”

This is an opportune time for CFOs to take up that challenge.

Up until Q1, about 15% of retail sales happened online. Now, according to UBS, that number is 25% — a bump to be sure, though perhaps not as large as one would expect. (Q2 retail sales should be a better barometer of how much more people are shopping online.) Still, between more online sales overall, the “consumerization” of B2B and some brands making easy returns a key component of their business models, a larger volume of returned goods may be the new normal for distributors, and a new source of stress on balance sheets.

Accepting returns will always be both a necessary offering and a cost center. Many companies spend between 9% and 15% of total revenue on returns, according to a report from UPS, but the number doesn’t need to be that high. Businesses can reduce the amount of money lost, time consumed and disruption fomented.

Distributors Foot the Bill

The chain of ownership for goods varies by business model, said Michelle Davidson, wholesale distribution industry principal at NetSuite. But in most cases, when a distributor receives products from a manufacturer, it owns the goods and takes on liability for returns.

“It could be a situation where the manufacturer and distributor are sister companies, and they are doing intercompany transactions to sell goods from one arm of the company to another,” she said. “Typically though, the distributor buys the goods and marks the products up accordingly to make a margin.”

The fact is, manufacturers simply don't want to get into the distribution side of the house. That also applies to contract manufacturers.

“They focus on making products and then letting someone else worry about sales, marketing and distribution,” she said. “Hence why there are so many manufacturers overseas, like in China, who then sell to American companies that sell the product itself.”

From a returns standpoint, a distributor may split the expense with the manufacturer. But that depends on negotiated agreements and the reasons for the returns.

“Most of the time, the distributor assumes all liability,” said Davidson. “Unless there was a manufacturing error, which in that case, the manufacturer will issue a credit of some kind. But if customers change their minds for other reasons, like they found the item for a better price or wanted an exchange, that sits on the distributor’s books.”

All the more reason why CFOs should be aware of contractual terms, and why reverse logistics, the practice of handling returns, is a major challenge.

In fact, even before COVID, this was the second- or third-biggest supply chain issue for distributors, according to Schijns, who was previously the channel chief at Verizon and chief merchant and services officer for Office Depot.

She suggests CFOs review supplier, distributor and retailer contracts that define rules around returns. The terms of these agreements vary depending on the size of the distributor and purchasing power of the retailer.

For inexpensive products, for example, a retailer may destroy or recycle merchandise, and the distributor issues a credit; this is often a more cost-effective solution for the distributor, too. Retailers can generally destroy a certain percentage of items, often between 1% and 5%, and likewise receive a refund.

“There are always common frameworks, and depending on the size of the customer, those rules get changed,” said Schijns. “So if you’re a distributor of a line and you want to sell that line to Walmart or Target or someone else, good luck with it being your return policy, because it’s not going to be your return policy. The stronger of the two always wins.”

Since large retailers can negotiate more favorable terms, they usually receive full credit for any inventory sent back to the wholesaler. A small or midsize seller, however, may have to pay a restocking fee.

Sometimes goods end up back at the distributor not because a consumer returned them or something is wrong with them but simply because of lack of demand. If Target ordered 100,000 units of a certain item to sell across 500 stores, and half of all those items have not sold after a few months, it may send back the leftovers. This is particularly true for apparel retailers, which will likely be hit hard by stay-at-home orders.

Beyond the initial financial blow of issuing refunds, distributors must then figure out what to do with these items. And, the middleman is often left holding the bag if goods show up in poor condition.

“The largest issue is the financial issue, the impact of something sold, returned, repurposed,” Schijns said. “Customers often don’t want to pay a restocking fee, particularly the bigger enterprise customers, and they’ll negotiate that out of their contracts and then send things back that are in … interesting condition and always blame the shipper.”

Maximizing the Value of Returned Items

Not all returns are created equal. The amount of money that can be recouped through primary or secondary channels varies widely based on industry, product, condition and price fluctuations around supply or season. Determining the best option is not always straightforward and will benefit from an analysis by the finance team.

Key factors include the ability to resell a specific product, its price, margin and seasonality, said Anna Pomerantseva, product marketing manager at reverse logistics software vendor Optoro.

There are three primary options to handle returns:

Resell through the initial channel: This is the best outcome, since the company may be able to sell the product for full price or close to. But the item must show up in like-new condition with all parts and accessories. It also must be valuable enough to justify the labor and shipping costs required.

Sell through a secondary channel: A secondary retail channel is a great option if an item has been used. Certain products may require repair or refurbishment before they can be resold, a cost to factor in. Resale value varies widely based on the industry and item, but it is generally at least 15% to 30% below the original price, and sometimes much less. While discount retailers and liquidators are the usual outlets for this inventory, retailers including Best Buy, REI and Nike have launched their own online outlets for these products. Whether that route makes sense for a B2B or D2C brand depends on its customer base, volume of returns and ability to manage the process, but it’s worth considering given the rise in online sales.

Destroy or recycle: Donating items for a tax write-off or sending them to a landfill is sometimes the best option based on a distributor’s margin on an item relative to the costs of transportation, inspection and restocking. Goods like used cosmetics and perishable groceries cannot be resold due to health concerns.

Again, finance teams are well-positioned to do a cost analysis of these options. Consider that the average markup for a distributor is 20% and typically tops out at 40%. So there’s not a lot of margin to work with.

Want Improved COGS? More Visibility, Fewer Touches

Maximize inventory visibility across channels: Returned items must go back into inventory immediately. “A buy anywhere, fulfill anywhere, return anywhere” shopping experience offers the best chance to sell returned or remaining inventory at the highest price possible.

Minimize the number of touches: Each time an item is moved, it increases the COGS. Enabling drop shipping for online orders from brick-and-mortar locations will save the costs of shipping an item from the store to the warehouse and then to the customer.

Time is also of the essence, especially with highly seasonal items, like apparel, that depreciate quickly. A brand-new winter jacket may be worth half as much in April as it was in November. Similarly, electronics can become outdated quickly.

“Mismanaged returns can result in items piling up in warehouses or backrooms,” Pomerantseva said. “An item often loses value during the time it takes to be processed.”

Returned items also lose value as they’re sorted. Goods may be sent to three to five consecutive secondary locations, including retailers, liquidators, donation centers and landfills, before finding a final home.

“This inefficient system costs retailers money as it racks up extra shipping and labor costs during each step,” she said.

Tools to Make Returns Less Costly

To avoid that inefficiency, businesses need to develop a detailed returns process with clear steps for workers to follow. The system should guide an employee through that process, which can vary depending on the type of item, its condition and other factors. Does it need to be refurbished or cleaned before it can be resold? Should it be repackaged before it’s moved back to available inventory?

Meticulous inventory control is also essential. Barcodes and scanners paired with inventory management software allow for tracking the movement of merchandise and are good investments, especially in the age of omnichannel. When you have returns coming in from multiple channels, that creates more opportunities for lost, stolen or misplaced inventory. Any inventory management solution should be integrated with financials and order management, allowing a worker to quickly link a returned product to the initial sales order as soon as it shows up at the warehouse. This traceability is critical in determining the best next steps.

From there, a returns management solution can guide employees through the inspection process with a list of questions and instructions. Look for a system that can assess the item’s condition, seasonality and potential resale channels and suggest where it should head next. The software should also be able to track returns of specific SKUs.

“If we have a massive amount of returns on a single item, maybe we don’t sell that item anymore,” said Davidson. “What are the reasons that people are returning it? Is it because people changed their minds, is it because they just didn’t like the size, style or color? Is it because it malfunctioned? These are all things that feed back to your company to figure out what you should do next.”

Reverse logistics make up less than 4% of total supply chain costs, per the UPS report, and the insights gleaned from this technological investment in the returns process should more than justify the cost. Since returns are such a large cost center, even a small drop in the number of items returned or a slight increase in the average resale value can have a significant impact on the bottom line.

7 Ways to Reduce the Cost of Returns

At a time when every dollar matters to your runway, recovering as much income as possible on returned merchandise is critical.

Here are other ways to maximize your return on returns.

Retrain the sales team and partners. If an item is returned more often than expected, look at how the sales team is selling it and how marketing positions it. Often, nothing is wrong with the item itself — it’s just being sold to the wrong customers or for the wrong uses.

“Nine times out of 10, it’s because the sales force is mispositioning or mis-selling the item,” Schijns said. “If you can retrain your salespeople to do better on customer diagnostics and what the customer really needs, that’s step one.”

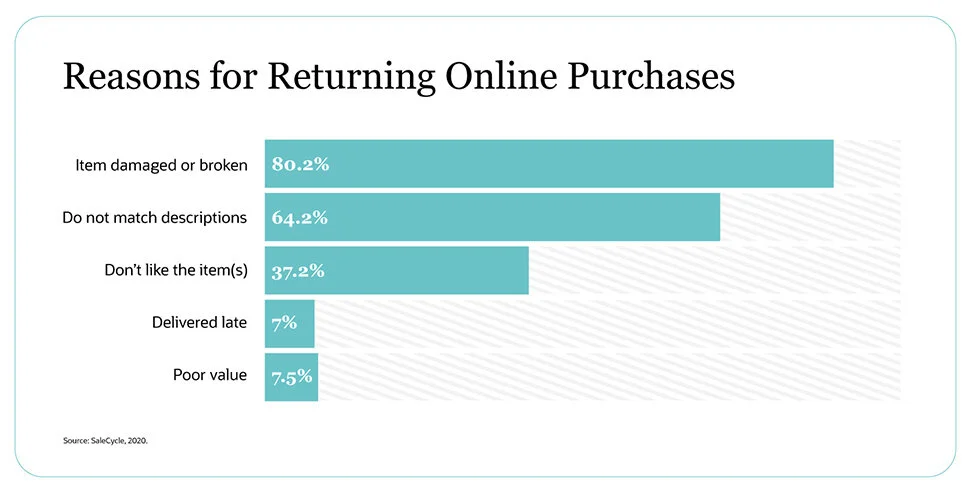

Davidson echoes that sentiment and estimates that 80% of returns stem from an internal problem, such as inaccurate descriptions by a distributor or the partner selling the product, or shipping the wrong items or quantities to a retailer.

Expedite and standardize returns processing. Returns must be handled immediately and efficiently to recover as much value as possible. Include return labels in shipments so your team can track packages, plan for their arrivals and inspect them quickly. All returns should be scanned or entered into your inventory management system upon arrival. From there, a distributor should have specific, documented processes for inspecting and restocking various SKUs. This will minimize both shrinkage and the cost of reverse logistics.

Before cutting a refund check, explore your options. Schijns suggests asking the customer if it will keep the product for a 10% discount or company credit. In fact, as we enter the “new normal,” distributors and retailers may consider rethinking their return policies altogether. For example, they could offer only company credits for returns of certain goods that may have been stockpiled, or charge a 10% restocking fee where contractually feasible.

“Too often, we look just at time, like we’ll allow a return in 30 days or 45 days or 60 days, or condition, versus how else could we handle it,” Schijns said.

Roberson agrees that businesses should encourage exchanges versus returns to offset revenue losses. That means making the exchange process as easy or easier than simply sending items back. This strategy is effective for apparel and footwear, where satisfaction may be a matter of going up or down a size.

“Returns are actually an opportunity … to retain more revenue and reduce costs as well as invest in their customer lifetime value,” said Roberson.

Don’t make immediate payment. Companies are often too quick to give clients full refunds before checking for damage, missing parts or anything else that could impact its resale value, Schijns said.

All returns should go through a thorough inspection. If the product is in worse-than-expected shape, contact the client and try to find a mutually agreeable solution. That’s a much better strategy than immediately giving the customer a full refund, then going back later to try to recoup losses.

Collect and use customer feedback and other data. Our most recent Brainyard executive survey showed that using data more effectively is a top priority for CFOs and line-of-business leaders. This is a perfect opportunity to put that into practice.

Asking customers why they’re returning something — and actually using that information — is critical to identifying issues, either with a product itself or how it’s being marketed or sold. Ideally a distributor will be able to sort by return reason and see the return/exchange rate for each SKU.

Use that data to shape future purchasing decisions, and work with the supplier to see if there is a way to resolve the issue. The quicker a distributor identifies a problem, the fewer returns it must manage.

Augment online product content. “The problem of returns starts at the checkout,” said Optoro’s Pomerantseva. This is especially true with online purchases, since the buyer cannot touch and feel the product. Mitigate this problem by offering more content: Multiple images, videos, detailed product descriptions and a Q&A section all contribute to lower return rates.

Along those same lines, your customer service team should be easy to reach and must respond quickly. A live-chat function on your ecommerce site could be a smart investment. The more the buyer knows before making a purchase, the lower the chance of a return.

Consider outsourcing returns. For some organizations, handing off returns to a third party is a smart play. Beyond avoiding headaches, it could reduce costs. A specialist, like Happy Returns or one of the many 3PL (third-party logistics) firms focused on reverse logistics, can bring to bear expertise and economies of scale, including better rates with carriers and more efficient processes tuned to the unique demands of the reverse supply chain.

The Bottom Line

Distributors are being squeezed by larger industry trends, like consolidation, increasing competition and direct-to-consumer manufacturers, as well as fundamental changes driven by a global pandemic. If there was ever a time to eliminate unnecessary expenses, this is it.

One of the most difficult parts of returns management may be balancing customer expectations with the bottom line. Adjusting a return policy to no longer give immediate refunds or, in some cases, offer only company credit could draw negative feedback. But these customer-friendly policies are simply less sustainable as retailers and distributors look for cost-cutting measures in an increasingly competitive and challenging environment.

CFOs looking to maximize liquidity shouldn’t underestimate the savings that can be realized by evaluating every step of the buying experience for potential improvement. After all, every return starts with a purchase.

“By thinking about returns holistically, from the time the item is purchased to when it finds its second home, retailers can suss out holes in their current systems,” Pomerantseva said.

Ian McCue is a content manager at NetSuite who also contributes to the NetSuite blog and Grow Wire. He previously wrote about supply chain challenges and technology at HighJump Software after starting his career as a sports writer. Reach Ian here.

Article was originally published here.